About two and a half years ago, I posted my thoughts, immature as they were, on what I suspected was the reality of self-rescue on a sailboat in the middle of the ocean. By "self-rescue", I mean a way in which the solo sailor, having fallen off, can reboard his/her vessel, or how a single and perhaps smaller member of a couple can retrieve the big dope that's slid overboard in the night.

It starts with understanding the difference between EPIRBs (a beacon for the boat) and PLB (a beacon for the body that has fallen off the boat). This video explains it succinctly:

It is quite conceivable that if you came up on deck 200 NM offshore to find your PLB-equipped crew missing, you would a) call a MAYDAY on your SSB and VHF, b) hit the EPIRB to get a plane in your general vicinity, and they would c) attempt to zero in on the PLB signal, which is normally weaker and of lesser range than a boat's EPIRB.

I was of two minds then, and I remain so today, with a couple of caveats and an evolving suite of MOB devices to blame for the rethink. My original position was, and remains, to stay aboard the boat. Sounds easy, right? Obvious, even. And yet people fall off boats all the time. On the Atlantic delivery I crewed after I wrote the original post on self-rescue and problems I saw with getting someone back aboard in bad conditions, the boat came off an odd and higher wave while the AP was on during my middle of the night watch. I had been watching the stars, so brilliant at sea and had been lying on my back. The boat slid, the cushion I was on slid, and suddenly my feet were under the lifelines and my backside was on the toerail.

Then the tether went twang. I stopped my slide with my feet washed by the waves of the sudden, clear-air gusts or rogue waves or whatever the hell it was that threw us over without warning.

I was able to quickly haul myself (and the cushion) back, switch off the AP, and actively steer back to our course. By the time the skipper appeared, all was well and I had re-engaged the AP.

But it was a lesson or a warning. I never failed to tether on in the Atlantic when on solo watch, because intellectually I understood that the likelihood of finding someone on a moonless night with 10-12 foot waves was pretty low. I could be pretty far astern, and injured, before anyone found me. The PLB might...might...have helped, but we were between Bermuda and the USVIs at about 63° West, and likely beyond SAR aid. Past Bermuda, I saw two ships, at a great distance. Maybe. Could've been a UFO.

So stay aboard. Don't cause your friends, or SAR personnel, or even your crewmates to play what I grimly termed "spot the corpse". Believe in your saviours: the tether, one hand for the ship, the PFD and the Personal Locator Beacon...wait, what about that PLB?

I still have that ACR "Res-Q-Fix" PLB. It lives on Valiente during the season, because while it's not an EPIRB, it's better than nothing. I wear it when I sail solo, again because it's better than nothing. But it's five years old now, and it's due for a battery replacement. I have to wonder, in light of PLB technology's "cheaper and more features", if it's worth bothering. (Since writing this, I found a place in Hamilton which will swap out the battery, so that and visiting HMCS Haida are reasons to go to The Hammer.)

The manual operation aspect is an issue, as well: If you are knocked out or have broken fingers (not a crazy assumption if you were knocked off the boat), you are going to have issues activating some of these units once in the water. It's a two-hander job.

So are the new style of near-range "life tags" the way forward? That depends, I think, on comparing features.

This link from Practical Sailor tells us

I don't know if devices like these are practical, but as we creep closer to our own ocean adventure, I do consider them in the context of overall crew safety at sea.

While I agree that the majority of sailing done is coastal and within reach of such SAR resources as may exist, I am thinking specifically of offshore use, where the distance exceeds the range of SAR personnel, and the odds of a person being alone at the helm in the middle of the night is greatest, and it is this possibility of having to be the only possible rescue vessel in the area that I am thinking of.

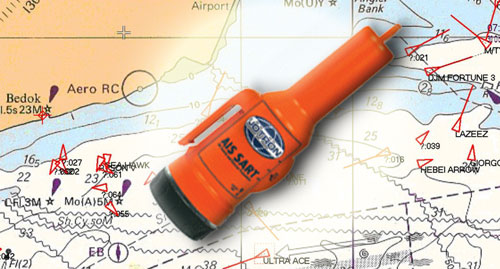

The short form is that these beacons incorporate AIS and DSC signals to aid boats in turning around and locating people in the water. They can sound an alarm if the wearer gets more than, say, a boat length away from the AIS.

It's interesting, even if the two-mile range seems short to me. Obviously, it's only for multi-person crews able to physically retrieve people from the water, which means that a) there's a ladder or Lifesling or other means of getting them aboard, and b) they aren't so injured that they are unable to aid in their own climb back on deck, and c) conditions allow coming alongside a person in the water without slamming them further or chopping them to bits with the prop.

Point goes to staying aboard. On the other hand, with a "proximity beacon tied to the AIS, you know if somebody is off the deck very quickly. Even if they are passed out and have a broken arm, guaranteeing a hard recovery, the search aspect would be the smallest part of the operation.

|

| Different AIS-SART, same hand? |

That aspect is better this than waving a sputtering penlight, I suppose. Yelling is right out. Anyone who's tried to shout from an aft cockpit to the bow where the anchor handler is knows this is true.

On the other hand, in a heavily trafficked area such as Lake Ontario, I actually would prefer what I already have: a submersible VHF with which I can directly shout MAYDAY on Ch. 16. My Standard Horizon 850 gives me not only a radio that can float/take a dunking, but can also give me a lat/lon thanks to an integrated GPS. The likelihood on a summer's afternoon near Toronto is that I would be hauled out by another boater monitoring Ch. 16 and halfway back to my own boat before I saw the yellow helicopter.

But that's not really the scenarios for these gadgets. They are more-or-less designed for offshore. More presumptions include that:

a) all crew on deck are wearing these devices at all times.

b) the devices themselves are always charged and functional, meaning they are "always on" in a sort of "guard mode" until lack of proximity to the AIS transceiver sets them to "active mode".

c) that you keep your AIS on continuously in order to hear the alarm.

It may be the case that the ideal solution is for a PLB/GPS combined with a two-mile COB beacon, allowimg the greatest number of options for "self-rescue" or thanks to the more typical guys with the slings in orange helicopters. I wonder if a simple clamp and extending, brightly coloured pole (like the sort on bicycle carts) on the PFD would increase the visibility of the COB and, if the beacon was on the top of a two-meter pole, would the range of the beacon then be much greater than two miles? I understand also that some PFDs inflate a "soft danbuoy", a sort of inflatable, brightly coloured plastic pole that deploys off one shoulder. That seems like a good idea, but would be only marginally better at night.

That "laser flare" is looking good at this stage. Certainly, what I currently have is enough for Lake Ontario (mostly) fair-weather sailing. But I follow developments with interest, as do I check up on the international standards.

|

| It only looks like a bottle of rum |

This AIS-SART technology looks promising, but is it translatable to the self-rescue set-up we are discussing? Dunno. Must learn. Maybe this would serve. It calls your VHF using Channels 16 and 70 via DSC, providing a set of GPS lat/lons. It also has a strobe and can be water-activated.

The "old school" trailing floating rope is an old trick from the days of cork-filled "life belts". I have read of a couple of cases where it worked (for obvious reasons, you don't hear about when it doesn't work). A refinement of this idea is attaching this trailing line via shock cord and a sort of pin and block to the control lines of a wind vane. The weight of the line is not sufficient to pull the pin, but the weight of a body on that line, being dragged at several knots, is. You pull the pin, the wind vane is disengaged, and the boat (hopefully!) rounds up. You haul yourself forward and hope you were clever enough to buy the sort of folding ladder you can deploy from the water's surface.

Again, you have to be fit and largely uninjured and conscious to accomplish this. If you've ever been towed behind even a dawdling sailboat, you know you'd have to possess considerable arm strength to pull yourself forward. Adrenaline might help, but if the water's not tropical, not for long.

You could rig this "release and round-up" to a jib sheet, too, but I would have to look up how that works in the old 'single-hander' books I have. It might be only suitable for dinghies.

Needless to say, these methods are in no way guaranteed, but if I was single-handing on the open ocean in relatively easy conditions, I would consider trailing a floating line aft. It wouldn't induce that much drag, and it's cheap, if "last chance" insurance.

It's an interesting topic, to say the least of it. People who "self-rescue" get to tell their stories. Rarely is a single-handed boat found adrift and uncrewed in which it's clear how the skipper departed, or why.

UPDATE, 2013.04.13: Of course, all these gadgets are predicated on being hauled back aboard in a timely manner, and from water that will slow the onset of hypothermia. Given the time of year from where I'm writing (early, fitful and sleety Spring), a reality check on falling into cold water is relevant. A couple of article by the excellent Mario Vittone on the equally compelling gCaptain website are worth linking here for the reality of hypothermia's role in complicating self-rescues, or indeed any rescue.

The Truth About Cold Water: A grim but honest examination about some of the myths concerning what a person can and cannot hope to do once off the deck and into the cold sea/lake. In my recent Marine First Aid course, we learned a bit about cold shock and cold incapacitation, and a little bit about post-rescue collapse. But I haven't been trained as a paramedic, just as a first responder of the most basic (and perhaps only) kind available. All I can do is be aware of these factors if a person I can retrieve is appearing hypothermic.

Drowning Doesn't Look Like Drowning: Just as movie heroes seem to have infinite bullets, and Batman's sustained more concussions than a thousand Sidney Crosbys, so many of us have a rather fixed idea of what drowning looks like. This idea is completely wrong, according to Vittone, and you do learn the truth in a proper marine first aid course.

UPDATE, 2013.05.06: Thanks to sailor and long-time reader John Cangardel for sending me this, which I suspect is based in part on a prop from a James Bond movie.

Interesting how at 1:43 the helo spotted him on the infrared...in the daytime. But I cavil. This is, like, the Garmin Quantix I mentioned earlier this year, a bit of a paradigm shift in PLB form factors. Interestingly, it's orientated to calling in rescue resources from afar, not the "self-rescue" discussed above. Is this therefore of most use to solo sailors?

|

| No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to drown. |

|

| If you sink this close to shore, skip the beacon and just get out and walk. |

According to this, the Emergency II will transmit for 18 to 24 hours. I am guessing it is both 121.5 and 406 Mhz because neither transmission contains a GPS string. I think an EPIRB with GPS wins in this regard, plus a SART for the last few miles.

I am also a little suspect at the length of time it will broadcast. Hit a container in the South Pacific and you could be in that raft for a few days, even with a working EPIRB and your location tracked via COSPAS. Interestingly, COSPAS-SARSAT frequency issues are discussed by Breitling, who maintain that the analog 121.5 Mhz signal is still valid for final "homing in".

I also question the need to secure the watch to the top of the raft (bring a C-clamp in the ditch bag, perhaps?), although clearly one cannot deploy the antennas and continue to wear the thing. I can see this being of some use to hikers, mountaineers and back-country skiers, perhaps...the sort of people unlikely to carry an EPIRB or even a standard PLB (although that is a good thing to consider if it's the 406 Mhz GPS transmitting kind).

Nonetheless, even a fifteen-grand, short-lived beacon you can wear will appeal to some. Not me, however: I wear a worn Suunto Vector with a cracked crystal, said crystal getting cracked in the first place because the Vector is somewhat chunky; the Emergency II is even larger and heavier. I like my old watch's barometer feature, however. but am considering switching up to a Suunto Core, which has a "storm watch" alarm feature some sailors have reported useful to them in getting sail off before bad weather hits.

| Dorky, yes, but I don't have to lash it to the top of the raft to use it. |

For fifteen grand, however, the Breitling Emergency II would just make me more nervous than the possibility of stepping off into the raft. I also can't help but reflect that I could spend the same amount and could ballast the liferaft with EPIRBs that would last a month.

Note that I would not in fact spend that amount. That's also about four very nice liferafts.

|

| This German-made AIS beacon starts transmitting when the PFD inflates, which is handy if you are unconscious, but alive, when you fall off the boat at 0300h. |