|

| The late S/V Concordia |

No, not M/V Costa Concordia. That particular case of death-by-cruise-ship/"showboating" is not properly in my purview, although there's an element of "horrible warning" to a number of its aspects that I suspect will be understood in the fullness of time.

I mean S/V Concordia, the Canadian "Classroom Afloat" sailing vessel that went down off the coast of Brazil. It's safe to say that at this stage, changing the name of our boat to "Concordia" is not in the cards. The name would appear to connote bad luck. And even though my wife has recently earned a teaching degree, I would hesitate to recommend floating teaching. Maybe after we cruise. Maybe.

It has been just over two years since the Canadian sail training ship S/V Concordia rolled beneath the waves off the coast of Brazil in February of 2010, and yet with surprising alacrity for a bureaucracy, Canada's Transportation Safety Board has issued a analysis report complete with conclusions as to what sank the relatively modern (built 1992 in Poland), and fully compliant from a safety point of view, 57.5 metre-long barquentine.

The important part of the story, of course, is that all 64 people on board made it into liferafts alive, and apart from a broken arm dealt to the ship's doctor, unscathed. Equally remarkable is that they survived nearly two days at sea in poor conditions before a rescue commenced, one that may have happened significantly earlier. Had communications between the Canadian SAR personnel who logged the automated EPIRB distress beacon been taken seriously by Brazilian SAR personnel (in this case, the Brazilian Navy) in a timely fashion, the survivors of the sunken Concordia might have been drier sooner: They were not that far, in rescue terms, from shore, and the area involved was reasonably transited by commercial vessels.

The first reports of Concordia focused on this aspect of the preservation of life, As well they should have: All crew were safely taken into liferafts for the most part with only minor injuries, and while they spent a day and a half in rolly, unpleasant conditions before being picked up by a merchantman, no one died, and the injuries, while unpleasant, were minor and given the manner of the ship's demise, almost miraculous.

But is it a miracle when everyone lives, or is it a predictable outcome of decent training and adequate provision of safety gear? S/V Concordia was, in tall ship terms, practically factory fresh: Built in Poland in 1992 as a steel barquentine, Concordia was modern and well-equipped with a generous diesel to push her along when the wind failed. There was plenty of safety equipment aboard, and enough to accommodate all hands even though some of it was made inaccessible or unusable due to the rapidity of the ship's knockdown and the subsequent downflooding through open hatches.

About that knockdown/capsize:

|

| This suspect was cleared |

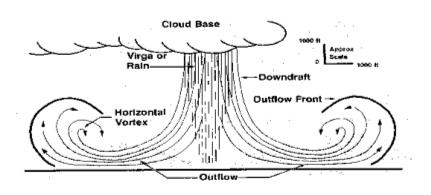

While initial news reports suggested that a squall-born microburst may have put Concordia over, a Transport Canada report on the sinking suggests that a combination of too much sail up may have laid the ship over to the point where the sea could downflood hatches that should have been closed. "Since the vessel was not fully secured as the squall approached, water entered the hull when it heeled. This compromised the vessel's righting ability to such a degree that it was unable to recover from the knockdown. As a result, downflooding progressed, causing an increasing loss of stability until the vessel finally capsized." (Transportation Safety Board Report on S/V Concordia, section 2.2) Thanks to astute reader Rick Spilman for correcting my eroded memory of this part of the report.

|

| This is a sign to close the damn hatches. |

As a sail vessel heels, particularly one with a small, non-angled rudder and little in the way of lateral keel to resist it, the opportunity to avert a capsize can diminish. Anyone who has been in a downwind broach will recall, likely strongly, the moment when the boat felt "detached" from the water and started to "skid". Capsize is related to this, and the "weight aloft" of a tall ship's masts means a generally lower tolerance than a typical cruising yacht, which tends to carry weight lower and farther below the water, comparatively, than a taller multi-masted, traditional hull boat. "Stability curves" inform the crew when the angle of heel, all things being equal, is becoming excessive. Concordia being a relatively new boat, and the math being well-understood, these curves were known. What is suggested is that the crew on the helm was not sufficiently well-versed to understand the approaching dangers.

One method of reducing heel is to steer head to wind. Another is to reduce sail and therefore the sideways pressure (assuming a beam reach) on the rig. A third is to release the sheets, a noisy and potentially sail-damaging move, but one most beginning sailors know. If you hold off until the boat or ship is heeled over too far, the rudder can no longer turn the boat, as it is no longer entirely submerged, and/or its angle is ineffective. This, it seems, combined with the unfortunate unsecured state of deckhouse and hatches for ventilation, meant that once the Concordia was over, she wasn't coming back.

Given that Concordia was a large, intrinsically top-heavy thing lacking the sort of keel/centerboard a cruising sailboat has), the question can be raised: Was there anything the ship's master and crew could have done to predict a sudden increase in wind, and did they have options to keep the ship from being overcome by these localized, "surprise" squalls?

|

| Regulations? Basically, arrive alive |

By way of analogy, we can look at history. It's been a mere 75 years or so since the last grain ships, large steel cargo sailing ships such as Moshulu, above, finally ceased to sail commercially just prior to World War II. These ships brought bulk goods such as fertilizer from Chile and wheat from Australia to (mostly) Britain. If you didn't mind waiting around 100 days, these lightly crewed, amenity-free behemoths could bring you a few thousand tons of raw materials or food at a price fractionally cheaper than a coal- or oil-burning freighter. Unfortunately for the crew, these frequently minimally powered (often only the capstan would be linked to a basic motor) and electricity-free vessels would have to go via the three great Capes of the Southern Ocean, Good Hope, Leeuwin and the notorious Horn, without even basic radio contact or much in the way of rescue services beyond sinking in sight of a beach you might wash up on before the fish ate you or the waves pounded you to chunks.

This video shot in 1929 by the renowned American tall-ship sailor Irving Johnson gives a taste of what life was like on a really large steel sailing vessel:

By contrast, Concordia had all modern navigational aids and access to weather information and search and rescue resources the tall-ship cargo haulers could only dream of. RADAR, EPIRB, VHF, SSB...you'd run out of letters before you could cover all the required and optional safety, navigational and communications acronyms Concordia carried. As a floating school filled with teenagers and crew, for the most part, not much older, their parents and the school's patrons would expect no less.

And yet certain hatches were left open in weather breezy enough to cause a steep heeling motion on a boat with little keel to resist it. One wonders if the hatches had been closed, and/or the sail reduced further, would the ship have come back from a squall-imposed knockdown, or have dodged the knockdown entirely? Couch commodoring aside, what are the lessons from a disaster that, arguably thanks to proper drill and seamanship after the knockdown, saw no one die?

I think dogging down the hatches would have helped. I think a willingness to sweat it out in a sealed boat, unpleasant as that may be, should be a first choice if the seas merit it. I think that perhaps boats like this should have fin keels or other means to increase positive stability and to lower the CG.

If that cannot be done, perhaps better training and a willingness to call the captain on deck should the heel exceed a certain angle. The second officer, according to the Transportation Safety Board report, was in fact deemed competent and possessed all the certifications required for doing his job, but those certifications do not delve deeply into concepts of stability and "squall curves". Why would they? That's sail stuff, and that doesn't count, does it?

"In order to gain this competency, masters and officers of sailing vessels would benefit from formalized training that specifically addresses the interpretation and operational use of the stability guidance provided to them, which, in this case, was the squall curves. Without it, they may not be able to interpret and make effective use of the critical guidance information when it is provided in stability books." (Transportation Safety Board Report on S/V Concordia, section 2.4)

I also think the tax dodge of foreign-flagging may obscure the ability to get to root causes of accidents of this nature, but that is perhaps an issue beyond my scope here.

|

| One type of "other means" can be seen amidships |

A boat built to look like a state of the art 1892 cargo barquentine...in 1992...need not preserve aspects of the original design made when wooden three-masters would have to enter tidal harbours. Not in 2012 or any year to come. Even a centerboard dropped 12 feet at sea might have kept this vessel upright via lateral resistance long enough to resist capsize. Examples exist of quite large boats with lifting keels. It has never been explained to me why traditional designs could not have something similar (apart from cost). Smallish (under 100 feet) Thames and North Sea sailing barges going to and from the Netherlands well up shallow rivers still sport "leeboards" which, while unlovely and not particularly hydrodynamically ideal, drop from the gunwhales to provide the lateral resistance critical to stability in a seaway, particularly in a shallow-draft vessel.

|

| A relatively modern take on leeboards: Ted Brewer's 1979 "Centennial Sharpie" ketch |

I do not contend that leeboards or lifting keels for sail-training or similar "tall ships" are the answer to the problem of capsize, but I do contend that they are an answer, as is a better understanding of what the "squall version" of vanishing stability for such designs may be. Being a charming, old-timey type of ship does not preclude the sort of scrutiny or engineering engagement to which all modern sea-going designs are subject. If we can make charming safer or less prone to sinking, we should not hesitate to do so. The sinking of Concordia was in many ways similar to the sinking of Pride of Baltimore in 1986, and of which I reviewed a book in my "sea books" blog. I would say training and EPIRBs made the difference, but the fact is that these tall ships still exist and still stand into the various forms of danger the sea can produce. One needn't drown for it if drowning may be averted.

|

| Not in picture: The Brazilian Navy |

The S/V Concordia tale ended with what seems to me to be an unnecessarily long sojourn in life rafts. Arguably, this was due to miscommunication between the marine rescue services of Brazil and Canada, but why such miscommunication existed is still not explained. In addition, the Brazilian SAR services seemed focused on the potential of the rescue as a media event and an opportunity for self-promotion; the actual rescue was performed by a merchant vessel.

The obsolete signal "S.O.S" might need to be revised to "Save Ourselves Sooner" in the sense that we who wish to go to sea in small, private vessels must look to our own resources and skills to preserve ourselves in the face of nautical disaster. It may be short-sighted to assume that one's 21st-century gadgetry will work properly in the first place; will be acknowledged in the second; and, having been acknowledged, will be acted upon in a timely and effective fashion.

Those life-preserving links exist, thanks to man's ingenuity, but the links are weak, thanks to man's inefficiency and, perhaps, institutional indifference. Better to stay on the boat, and in order to do that, it is better to dog down the hatches, seal the ventilators, and learn to recognize, by eye, instrument or RADAR, what may lurk in that approaching squall line. You may not be able to avoid a sinking, or as good an end result as did the people aboard Concordia, but you might give yourself a better shot at extricating yourself from a bad situation than the option of awaiting rescue in a rubber raft hundreds of nautical miles offshore.