Perhaps more to the point for those expecting

to rely on investment income and/or pension schemes to finance their sailing plans,

we collectively seem to have trouble counting past dos cervazas, and this general

innumeracy is allowing a

numerate elite to either

fleece us in the name of capitalism, or to simply arbitrage crisis after manufactured crisis, knowing that if we can count to Octomom, we are liable to forget things like poorly vetted

corporate bailouts and the "guarantee" of

undercapitalized entitlements. I'm using American data because

they clearly as a nation have lost the ability to count, or to distinguish the colour red from black, but

the same could be said for the EU and, if only to a lesser extent,

Canada.

|

| Here's where, if you can read, you can read about how you can't count |

The common thread is the absence of political will to stop making unfunded promises, and

the absence of actuarial acumen necessary to see which promises, in light of anticipated risk, make any sense to be making in the first place. Sailors can learn a lot from books on investing and gambling, by the way, or by hanging out with actuaries, which I would not have naturally assumed before I reacquainted myself with the math and probabilities that are a common feature of life on the water.

There is also what I, and

quite a few others, refer to as

the problem of scale: People evaluate risk not on the basis of quantifiable observation, i.e. data, but on emotional responses to perceived dangers (see the

evolution of childrens' playground equipment). As an aside, my wife, a reasonably rational biologist with a Darwinian turn of mind, has suggested that the upper middle-class habit of

having fewer children or just one child later in life has, to put it bluntly,

made them more precious than would be the case historically. A horde of unruly, undersupervised crotch spawn are, evolutionarily speaking, somewhat more expendable, even if few people wish to think of their offspring in such species-wide terms.

Precious snowflakes are therefore precious because, like snowflakes, they are perceived as being one-shots, unique, and singular. This is the perception, despite the fact that we live in a world with over seven billion people, top of the list of sound reasons not to have two or more kids. Hell, our Western society arguably

doesn't really like them in the first place. But if you only have one, the notion that the world is a perilous place for tykes to teens can be pervasive.

Where this factors into risk, and more specifically,

the risks of world cruising, is that despite teaching my kid to swim and watching him regularly turtle sailboats in order to reboard and bail them out since age 7, our decision to "take a child to sea" still elicits occasional critical comment

a good five years after I first bitched about it. My unproven contention, based on a sample of one, is that the

occasional plummet from the monkey bars of life is salutary and

instructive. I don't want to endanger my son, but I feel a limited amount of potentially dangerous activity teaches him to recognize new dangers more easily. Besides, the contention that life ashore is safe and going to sea will get us, or our son, drowned ignores

the quantifiable risks of daily life for a young person ashore, many of which are merely new and technically complex ways to

demonstrate bad judgement and the effects of peer pressure. It also fails to recognize the conceit that a child missing the opportunity to haunt malls and basement "media rooms" in a depressive and confining teenaged funk instead of touring the world shows an appalling, to me, self-regard as to the worth of

what we all laughingly call a life.

Even if bourgeois homebodies of my acquaintance aren't secret binge drinkers, they are probably drivers. People get into cars every day, perhaps even mulling over how that crazy boat restoring guy is to drag his wife and kid off to some Third World hellholes to get kidnapped, raped and killed by terrorists, and maybe not even in that order. Perhaps

those same people are killed on the highway. Crazy Boat Restorer Family sails on, bereaved, occasionally becalmed, but breathing.

Clearly, many people who know boats see less risk. Many people are supportive, and it's a rare day aboard (in the parking lot until late April) that I don't get a query about our progress. Still, it's clear that we as a society have explicitly accepted that the perceived freedom of driving on highways (or in America, to

have a nearly 1:1 ratio of guns to people, I suppose) is worth the risk of owning such devices and accepting the rather immutable physics involved. The difference from accepting the same sort (if not degree) of risk in sailing is that for a car crash or a gunshot wound, there is an extensive and usually prompt response from various rescue personnel; doctors are, in fact, standing by. Throw in airbags and seatbelts, and

it is much harder to die in a car than it used to be. Conversely, I suppose, speed-obsessed idiots can now go higher velocities without getting culled from, and thereby improving, the human herd. Win some...

By contrast to the ambulances and cops and Jaws of Life available to pry the doomed driver from her metal coffin,

the sailor is effectively alone. Short of developing SAR-based methods of teleportation, and beyond a rather modest radius of range,

there is no way to get from shore fast enough to prevent a drowning, and even reaching a boat in a timely fashion is dependent on inding and alerting nearby ships capable of diversion. As often as not, they find some debris and a small slick, and that's if the distressed vessel's crew activated some sort of floating beacon. Even today,

fully equipped sailors and their modern boats can disappear without a trace, leaving nothing but informed speculation.

If this is the possibility with modern boats, imagine the risk evaluation required with

a 52-year-old wooden replica built for a movie.

|

| The end of a wooden world. |

This is, or rather, was

Bounty, built in 1960 for that year's remake of the famous tale of mutiny, breadfruit and alleged quarterdeck tyranny in the South Pacific. When it sank off the east coast of the U.S. in the vicinity of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, it was thus three years older than

Bluenose II. This is a wooden replica schooner itself so ravaged by time and the sea that it has recently been rebuilt so extensively that

some question whether or not it can be considered the same vessel.

Here's the thing about tall ships, at least the ones planked in wood and sealed with caulking irons, oakum and some modern version of pitch: they take vast amounts of skilled labour, gear, constant maintenance and sacks of money to keep afloat. This is because wood was about the only option for warships much bigger than a

coracle. It is not because it is a trouble-free or potentially easily compromised material,

particularly given traditional construction techniques and

issues inherent to using wood as a

ship-building material.

While all ship-building nations knew of wood's shortcomings, it's not as if there were alternatives before technology had advanced to the point of

manufacturing plate iron and steel. Building and maintaining say, a navy in light of knowing these shortcomings (including a practical limit to length and average lifespan) meant extensive assessment of risk and its

mitigation through practical measures. The Royal Navy's triumphs during the Napoleonic Era, for instance, were not primarily a function of stout-hearted tars within superior ships, as the Royal Navy generally had a greater number of slower, if

perhaps better-built designs, but

rather of the vast network of supply and services, and a logistical committment second to none. You could have a great navy only with

shipyards placed strategically to

victual,

repair and restock them. Some

notable battles were fought with an eye to preserve RN supply lines, and less to bloody Boney's nose.

Despite all the triumphalism, the cost of having a Royal Navy both large enough, skilled enough and serviced enough to essentially blockade the rest of Europe

nearly broke Britain's economy. By contrast, today's wooden ship replicas are not at risk from cannon-fire and do not feature impressed crews, but they still are vast sinks of money and sponges of skill,

merely to keep them afloat.

As can be learned from

Mario Vittone's excellent reportage on the professional mariner-oriented

gCaptain site, perhaps the old

Bounty was

neither crewed to the level of seamanship required by wooden ships, or perhaps any ship; nor was it

maintained or

skippered in what we might evaluate as

a risk-averse manner. As usual, money might end up being the issue. Even in our modern age, with (presumably) more regulatory oversight, insurance surveys and general engineering-based critical thought than was the case aboard the average Royal Navy frigate of two centuries past, it always comes down to money and the willingness to defer maintenance or use the wrong materials or hire "cheap and strong" as required. One of the key takeaways of most tall-ship operations of which I'm familiar is that new crew love the romance of big sail, but that as those experiences are comparatively rare, there is a question whether the skills such crew learn from the "tall-ship pros"

are in fact the correct skills through which they can safely work the ship in all conditions.

Even though the

Bounty inquest's conclusions lie in the future, much of what I've read so far reminds me of the fate of

Pride of Baltimore, which I

covered in my boat book blog a few years back.

|

| We think we've learned a lot since this fed the fishes, but perhaps we haven't. |

A point that Vittone,

himself an experienced U.S. Coast Guard member and a clear, concise writer, made about the call of the

Bounty's captain to take the ship out to sea instead of battening down in a relatively close hurricane hole, is, in the context of how we manage risk at sea, worth quoting in full.

"[The captain of Bounty] had faced down storms before and won, he had tangled with hurricanes and made it home, his experience

was that if he headed into harm’s way, he would get away with it. He

had clearly confused the lack of failure with success, [my emphasis] and may have

begun to truly believe his own advice."

Given my own comparatively limited time at sea, and the zero time spent on wooden ships apart from visiting the things on nice summer days, I'll risk being considered an

armchair admiral when I state categorically that

Bounty had no business taking a worn and ill-equipped tall ship with a green crew, dubious maintenance and no real reason to be there into the teeth of one of the largest hurricanes on record. I thought that strongly when I heard the news and saw

Bounty's decks awash, but the current proceedings underline it in red streaks.

In the captain's experienced deck shoes, however, would I have done differently? I like to think so, because I feel I possess the requisite suspicious, gloom and paranoia of the undrowned skipper. I expect, if not the worst, things I haven't planned for, but for which I must, in my attempts to mitigate risk, have a response, from the level of "this chewing gum will serve until port" to "step into the raft, dear".

But I can't be sure. Like this

notorious incident of a hot-shot pilot overestimating his skills and underestimating physics, a record of dodging bullets may promote an entirely illogical contempt for them, or conversely, a belief in one's own immunity from their effects.

Eric Tabarly's fate comes to mind, too. Perhaps

experience can breed a complacence that is dangerous, but that approaches in tiny increments.

|

| A touch beyond the AVS, alas |

Needless to say, incidents like those of

Pride and

Bounty (and

Picton Castle and

Concordia and even the race boat

Wingnuts), so clearly filled with nautical and mortal consequence, focuses the mind. It should encourage a sort of heightened safety awareness, like that possessed by the manager of a fireworks factory, I suppose.

Aboard, one is surrounded by minor hazards that must be recognized and managed, and occasionally practiced for (I've changed a seacock in the water...it's a process with almost more drama than water, and there's a fair bit of water). To lessen the risk of a

single source of knowledge and skill aboard going down with injury or worse, for instance, my wife is taking a diesel repair course and I am taking a course in Marine First Aid and CPR. It's a neat reversal of our accustomed roles, as she is clearly going to be the ship's doctor, and I have grown comfortable with engine arcana. But we both feel that the mitigation of risk relies on both similar and complementary skill-sets. Anyone standing watch alone, at night, in a gale, must be able to work the boat for that watch, unless a real emergency arises. Learning how to distinguish that from something that can be safely ignored until watch-changeover, or which can be fixed sufficiently with self-adhering tape or a reef knot or two, is part of the seamanship all must possess or must be in the process of acquiring.

|

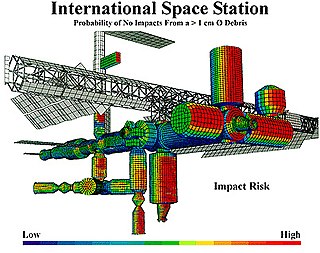

| More complex than the average passagemaker, but the ratio of awash containers to fist-sized meteorites is probably similar. |

So one of the

keys to managing risk at sea is to have a proper context.

A boat can be made only as safe as the habits of mind of skipper and watchstanders and crew allow. Some boats are run in a relaxed, seamless fashion...and then you see loads of labels, clearly marked stores of spares, secured stowage of tools and provisions, and you are shown the part of the log with the schematic where all the fire extinguishers are located, and the instructions for running the engine from a cold start that a second-grader could follow. Crew members will be seen testing hatch closures or walking the deck at dawn looking for pins or fasteners that have worked loose in the night. There is a culture of risk management aboard.

There is seamanship. That's how I define it, not just as the ability to splice or

to do knots or flaking down lines or knowing when to reef, hand and steer. It's a bit more holistic than that, and it centers on risk reduction.

Other boats aren't

obviously unsafe, but there may be seen a series of minor malfunctions, clearly past-due gear, pre-emptive jury-rigging, or just too much rust or wear for comfort. There's a lot of quite old boats still sailing on Lake Ontario, because freshwater is kind to fibreglass, but if I spot a 1970s gate valve below a boat's waterline, for instance, or single, non-stainless steel hose clamps in the head intake, I may elect not to crew with that vessel. Sailors of even basic experience know that gate valves, particularly old, rarely worked ones, canstick and were usually made of zinc-leaching, hardware-store-grade brass. We know that non-SS clamps rust and fail and sink boats at dock (I have seen this more than once at my own YC). It's 2013. Finding brass gate valves and hardware store single clamps on a boat has just told me that the skipper manages risk, if even consciously, in a haphazard or slack fashion, or, if I wish to be precise, in a fashion below which I care to participate. I must have a streak of bean-counter in me, or it's just an aspect of boat ownership I've developed, as pennies have had to be watched

very critically.

|

| Perhaps the finest account of red-blooded, lusty nautical book-keeping ever made |

Another wrinkle is that risk management also has

an element of psychology in it. Careless or underinformed sailors fail to drown or lose their boats every day, but when they do, it is not entirely unexpected. I could supply a list of people for whom a nautical misfortune would not be an entirely unexpected event...but then why should the sea be different from the land in that respect?

And there's the secret, really:

If you can recognize risk, and

through forethought, preparation, maintenance and simple prudence can manage it, you are probably

safer alone in the high latitudes than you are in the waters off Miami on a holiday weekend, because you aren't surrounded by people in heavy vessels who are not, or who are incapable of, managing risk.

This

risk-awareness and management is clearly a process, however, and it can start as simply as the keeping of logs or checklists. I started this years back, mainly because I needed to think more schematically about what I had examined, fixed, serviced, lubed or reattached in the right order. Weirdly, the act of logging or ticking off a list means I rarely need to consult it again. I was driven to this habit, however, by early screw-ups of variable severity. I have been shy in this blog about listing most of my rookie or even hubristic and potentially fatal errors, but there have been some

doozies, which I may one day be brave enough to share in the spirit of being a horrible warning. Providence preserves, however; I persist, older, with a few interesting scars, an even number of fingers,and, I hope, a touch wiser. I feel better equipped, thanks to at least a partial recognition of what I'm dealing with, to approach the challenges, both physical, mental and human, of the risky, but maybe not

that risky, business of voyaging.

|

| Arr, there be a reckoning ahead... |