|

| Ironically, this book arrived by truck and then by foot. |

To the average, non-mariner citizen, how the shelves at their local Walmart (or slightly less proletarian vendors) are stocked is of little interest. There's underpaid people in the front and presumably tractor-trailer docks at the back, the denizens of which labour in obscurity to bring consumers their discount-priced crap.

Rose George begs to differ: In "Ninety Percent of Everything", she gives (to me, anyway) a compelling recap of the "invisible" industry of global shipping, which has been revolutionized both by the internationalization of shipboard labour and ownership, and the related decline of national merchant navies, and the near-total acceptance of the container as the "base unit" of world shipping.

|

| It's getting crowded out there. |

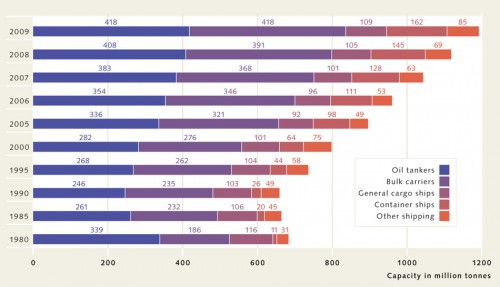

Rose recounts how world commerce got here, and how the shipping container, after much industry resistence and vast investment to alter the world's harbours, became the de facto standard for the transshipment of manufactured goods. While raw materials, grains and liquids are shipped in different types of ships, and while container ships are not, in terms of the world's shipping fleet, particularly numerous, they are often the most noticeable, and, unlike tankers or bulk carriers, those containers can and do fall off. George relates that while only 6,000 out of 100,000 vessels of the world's merchant fleet are container ships, there's no point in building them small as their economies of scale dictate that the price of moving a container's contents (already ridiculously tiny) is reflected directly in how much of it can be hauled in one go.

|

| The diesel engine of M/V Emma Mærsk:You know that when your engine requires sets of stairs, it's pretty big. |

Speaking of economy, shipping is the greenest way per capita to get goods halfway around the planet. Having said that, however, the capita of shipping is so large, and the typical low-grade fuel they burn so dirty, that it's estimated that just 15 of the largest ships emit soot to rival all the world's cars.

|

| And it's prettier, too, even if its cylinders aren't the size of bachelor apartments |

Eager to concretize George's data in terms I could appreciate, I ran some figures for M.V. Emma Maersk's monster house-sized Wartsila Sulzer RTA96-C diesel engine when compared to my own wee diesel. Now, to be fair, I run standard diesel of the rather clarified, low-sulphur type used in cars and trucks, whereas most ships, including most cruise ships, burn a tarry substance known as bunker fuel.

|

| Guess which one is more polluting? |

Emma Maersk's most economical fuel consumption is 1,660 gallons of heavy fuel oil per hour. Let's say that the distinction between "Imperial" or "U.S." gallons doesn't really matter here. That's 0.260 lbs/hp/hour, according to the manufacturer. My Beta 60, by contrast, burns 4 litres/hr at 2,000 rpm. So pushing Maersk around combusts roughly 0.5 gal or 1.86 L of fuel per second, whereas Alchemy is more like 1 mL/sec.

|

| Oh, buoy, that's a lot of soot. |

What bollocks, of course: Alchemy is a 16 tonne, 12 metre sailboat fit to carry perhaps four souls and two tonnes of fuel, water and provisions. Not to mention that Alchemy's diesel is an auxiliary, and, unlike that of a container ship, is not required to run for weeks at a stretch. All of which is true, but the reason that ships use low-grade fuel of high polluting potential is the same reason they hire (when they hire) crew out of the developing world: it's cheaper to do things that way. And price, like most human commerce, is the break point of doing shipping at all.

Speaking of the developing world, George spends a lot of time discussing the blend of opportunity and plight facing the most numerous members of world shipping crews, the Filipinos. She notes it's a blend, because, just as the women of the Philipinnes seem to have self-exported themselves to the Wests in the form of nannies, nurses and caregivers, that country's men are found as the lower ranks of shipping crews virtually everywhere. The lower ranks only, for the most part, due to the relatively low grade of what George calls "marine academies" in their homeland, and in the fact that shipping seems to be somewhat socially stratified, with white Westerners at the captain level, and Indians in the engine rooms, with a smattering of Ukrainians and Eastern Europeans in the middle ranks. George doesn't question this much, except to note that there isn't much mixing among the crew.

Whether this is due to hierarchy or culture isn't clear, although if you are going to be ripped off, it's usually the lower crew who get, unsurprisingly, the dirty end of the stick. That's why there are still missions to seafarers: instead of shore leave, there are merely 24-hour turnarounds in semi-automated container-handling ports; the old sailorly lifestyle of going a-whoring and a-boozing in port for a week is largely history, according to George: the life of today's seaman is too tiring and rushed to go on shoreside toots, and never mind the cost of even getting out of vast ports miles from the fun of a city. So the missions fill the gap and provide small necessities and a respite from the ripoff artists that still plague the seaman's world once off the gangway.

"Nearly everything is transported by sea. Sometimes on trains I play a numbers game. The game is to reckon how many clothes and possessions and how much food has been transported by ship. The beads around the woman’s neck; the man's iPhone. Her Sri Lankan-made skirt and blouse; his printed-in-China book. I can always go wider, deeper and in any direction. The fabric of the seats. The rolling stock. The fuel powering the train. The conductor’s uniform; the coffee in my cup; the fruit in my bag. Definitely this fruit, so frequently shipped in refrigerated containers that it has been given its own temperature. Two degrees Celsius is 'chill’, but 13 degrees is 'banana’." -Rose George, Ninety Percent of Everything.

George, partially due to the language barriers of the multi-ethnic crew, spends a lot of time with M.V. Kendal's Captain Glenn, a man, in the book's setting of 2012, at the end of a 40-plus-year career as a professional mariner. He's proud of his ship and his service, but his perceptions of what the old world of "break bulk/general cargo" shipping was like before the advent of container ports would have been recognizable to my father, a merchant seaman in the 1940s and early 1950s, whereas today's strictly run (the captain is told from head office to increase or reduce speed to meet distant schedules, for instance) operation is more like an assembly line in a giant's Lego factory. The contrast of a man on the verge of retirement demonstrating to the uncomprehending author his mastery of the sextant, while at the same time acknowledging that his fellow sailors are treated "like the scum of the earth" is perhaps a telling marker of the degree and rapidity of how the shipping industry has changed.

George also discusses the shell game of merchant vessel ownership and the dubious practice of "foreign flagging" in ship registration. The practice of, say, "flagging" a ship owned by Greeks through various offshore shell companies, and yet flagged to various countries such as Panama and Liberia (or Mongolia!) avoids pesky safety rules and inspections of, shall we say, more developed countries. So much of the world's fleet is undersupervised and underregulated, or so George indicates, and this is because these torturous paper games are designed to save shipowners money. But it has real-life consequences when ships in bad repair wreck and spill toxic contents, or when (as George notes in another chapter), ships are hijacked for ransoms that may never get paid, and their cheap labour crews are left to rot and sometimes die.

The absurdity of the practice of flags of convenience in the modern world is unlikely to be altered, however: there's simply too much money in the scam. It does, however, lead to paradoxically odd situations, such as last month where the U.S.'s ancient Jones Act of 1920 meant that there aren't really enough American-flagged ships left in American waters to transport road salt from Maine to Boston.

|

| The "E-class" containship M/V Emma Mærsk: There are seven others just like her plying the oceans, and bigger ones on the drawing boards of global shipping. Photo (c) Mike Cunningham |

|

| Venus envy: Not big enough! |

And I for one, can't wait for containers to have AIS beacons.

Bonus link: the Elly Maersk set to a hypnotic beat.

Bonus link: The front fell off.