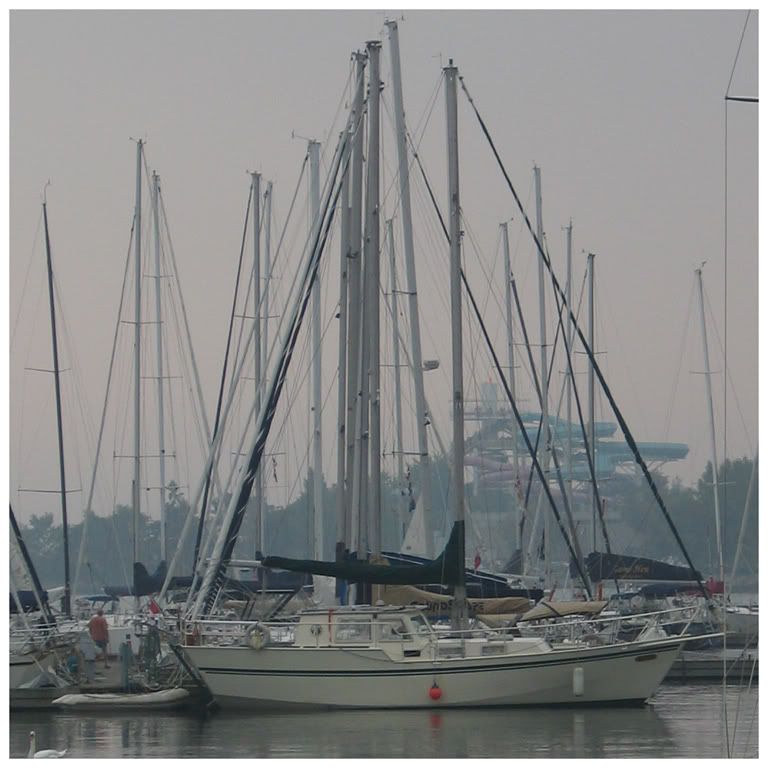

This seemed to be of nautical interest in this morning's paper...

Because this is

just too much

boat

for Lake Ontario

|

| The real thing, as sold by the redoubtable "Maine Sail". |

|

| Who left the dogs up? |

|

| Prevailing winds come in here. |

|

| The Beast with Four Cylinders |

|

| How mine looked originally. Now beaten to a still-accurate pulp. |

|

| The sextant is just to the left, behind the lead line and the cat o' nine tails. Y'arr. Etc. |

|

| Sure, nice watch, but telling the time is not enough for me, and I would worry about thieves, pooping waves and just dinging the thing all the time. |

|

| For the record, this isn't good. |

Tim was kind enough to give me a couple of "bayonet mount" lights and a foot-long strip of ganged LEDs to play with as an incentive to buy. Frankly, his prices are very good, so if the quality matches the ding, he'll be receiving my custom.

Tim was kind enough to give me a couple of "bayonet mount" lights and a foot-long strip of ganged LEDs to play with as an incentive to buy. Frankly, his prices are very good, so if the quality matches the ding, he'll be receiving my custom. With the incandescent 12 VDC "auto lamps" in use aboard most boats until the last five to ten years, you simply cannot leave them on for hours on end without running the engine, and its amp-producing alternator to recharge the batteries any more than you can leave a car's headlights on all day and expect the engine to crank. They convert 90% of their draw to heat to make that little tungsten wire glow, and heat up the boat (desirably, in some situations) in the process. Rare is the boater who hasn't overdrawn his or her batteries through miscalculation or mistake, and it can make for a sick feeling when the engine won't start...or starts in a dodgy fashion...because you've left the lights on too long.

With the incandescent 12 VDC "auto lamps" in use aboard most boats until the last five to ten years, you simply cannot leave them on for hours on end without running the engine, and its amp-producing alternator to recharge the batteries any more than you can leave a car's headlights on all day and expect the engine to crank. They convert 90% of their draw to heat to make that little tungsten wire glow, and heat up the boat (desirably, in some situations) in the process. Rare is the boater who hasn't overdrawn his or her batteries through miscalculation or mistake, and it can make for a sick feeling when the engine won't start...or starts in a dodgy fashion...because you've left the lights on too long.| I don't like single-use items, but these are cheaper than the batteries inside them and are great for dark corners. |

"ALBERT EINSTEIN never learned to drive. He thought it too complicated and in any case he preferred walking. What he did not know—indeed, what no one knew until now—is that most cars would not work without the intervention of one of his most famous discoveries, the special theory of relativity.

Special relativity deals with physical extremes. It governs the behaviour of subatomic particles zipping around powerful accelerators at close to the speed of light and its equations foresaw the conversion of mass into energy in nuclear bombs. A paper in Physical Review Letters, however, reports a more prosaic application. According to the calculations of Pekka Pyykko of the University of Helsinki and his colleagues, the familiar lead-acid battery that sits under a car’s bonnet and provides the oomph to get the engine turning owes its ability to do so to special relativity.

The lead-acid battery is one of the triumphs of 19th-century technology. It was invented in 1860 and is still going strong. Superficially, its mechanism is well understood. Indeed, it is the stuff of high-school chemistry books. But Dr Pyykko realised that there was a problem. In his view, when you dug deeply enough into the battery’s physical chemistry, that chemistry did not explain how it worked.A lead-acid battery is a collection of cells, each of which contains two electrodes immersed in a strong solution of sulphuric acid. One of the electrodes is composed of metallic lead, the other of porous lead dioxide. In the parlance of chemists, metallic lead is electropositive. This means that when it reacts with the acid, it tends to lose some of its electrons. Lead dioxide, on the other hand, is highly electronegative, preferring to absorb electrons in chemical reactions. If a conductive wire is run between the two, electrons released by the lead will run through it towards the lead dioxide, generating an electrical current as they do so. The bigger the difference in the electropositivity and electronegativity of the materials that make up a battery’s electrodes, the bigger the voltage it can deliver. In the case of lead and lead dioxide, this potential difference is just over two volts per cell.

That much has been known since the lead-acid battery was invented. However, although the properties of these basic chemical reactions have been measured and understood to the nth degree, no one has been able to show from first principles exactly why lead and lead dioxide tend to be so electropositive and electronegative. This is a particular mystery because tin, which shares many of the features of lead, makes lousy batteries.

Metallic tin is not electropositive enough compared with the electronegativity of its oxide to deliver a useful potential difference.

This is partly explained because the bigger an atom is, the more weakly its outer electrons are bound to it (and hence the further those electrons are from the nucleus). In all groups of chemically similar elements the heaviest are the most electropositive. However, this is not enough to account for the difference between lead and tin. To put it bluntly, classical chemical theory predicts that cars should not start in the morning.

Which is where Einstein comes in. For, according to Dr Pyykko’s calculations, relativity explains why tin batteries do not work, but lead ones do.

His chain of reasoning goes like this. Lead, being heavier than tin, has more protons in its nucleus (82, against tin’s 50). That means its nucleus has a stronger positive charge and that, in turn, means the electrons orbiting the nucleus are more attracted to it and travel faster, at roughly 60% of the speed of light, compared with 35% for the electrons orbiting a tin atom. As the one Einsteinian equation everybody can quote, E=mc2, predicts, the kinetic energy of this extra velocity (ie, a higher E) makes lead’s electrons more massive than tin’s (increasing m)—and heavy electrons tend to fall in and circle the nucleus in more tightly bound orbitals.

That has the effect of making metallic lead less electropositive (ie, more electronegative) than classical theory indicates it should be—which would tend to make the battery worse. But this tendency is more than counterbalanced by an increase in the electronegativity of lead dioxide. In this compound, the tightly bound orbitals act like wells into which free electrons can fall, allowing the material to capture them more easily. That makes lead dioxide much more electronegative than classical theory would predict.

And so it turned out. Dr Pyykko and his colleagues made two versions of a computer model of how lead-acid batteries work. One incorporated their newly hypothesised relativistic effects while the other did not. The relativistic simulations predicted the voltages measured in real lead-acid batteries with great precision. When relativity was excluded, roughly 80% of that voltage disappeared.

That is an extraordinary finding, and it prompts the question of whether previously unsuspected battery materials might be lurking at the heavier end of the periodic table. Ironically, today’s most fashionable battery material, lithium, is the third-lightest element in that table—and therefore one for which no such relativistic effects can be expected. And lead is about as heavy as it gets before elements become routinely radioactive and thus inappropriate for all but specialised applications. Still, the search for better batteries is an endless one, and Dr Pyykko’s discovery might prompt some new thinking about what is possible in this and other areas of heavy-element chemistry."

Here's a bonus link for those readers who, like me, have found how refitting a boat has been an exercise in the history of technology, i.e. no matter where you are aboard, some fluid needs pushing uphill for some reason. As a result, one learns about hydraulics and physics, AND one gets wet. Thought I might say "or" there? Wrong. The skipper get wet even when he doesn't screw up once. It's "Neptune's fee", I suspect.

Anyway, behold The Toaster Project: one man's quest to smelt a humble chunk of technology.

Whether this is all a good thing or not remains to be seen. As a Canadian who has "push-started" more than one frozen car back to life down various rural roads in winter, I prefer systems I can repair or work-around. In the context of this discussion, slab-reefing, horizontally battened mainsails are "manual", and the various types of in-mast are "automatic".

Whether this is all a good thing or not remains to be seen. As a Canadian who has "push-started" more than one frozen car back to life down various rural roads in winter, I prefer systems I can repair or work-around. In the context of this discussion, slab-reefing, horizontally battened mainsails are "manual", and the various types of in-mast are "automatic".

Whatever the tenuousness of the analogy, I do not at this stage believe that in-mast can, in most cases, match the performance of traditional, "roachy" mainsails. I do believe there are ways (stackpacks, jacklines, certain batten car designs) to make "manual" main handling more efficient. I also believe that, having sailed in-mast reefing boats in the heaviest winds I've experienced at sea, that they are viable, durable and dependable...not to mention very quick...methods of reducing sail.

Whatever the tenuousness of the analogy, I do not at this stage believe that in-mast can, in most cases, match the performance of traditional, "roachy" mainsails. I do believe there are ways (stackpacks, jacklines, certain batten car designs) to make "manual" main handling more efficient. I also believe that, having sailed in-mast reefing boats in the heaviest winds I've experienced at sea, that they are viable, durable and dependable...not to mention very quick...methods of reducing sail.

Anyway, geomagnetism and its role in navigation continue to attract my attention, even more than "do you know how to rewire an alternator?". Which to be honest, is probably something I should pick up.

Anyway, geomagnetism and its role in navigation continue to attract my attention, even more than "do you know how to rewire an alternator?". Which to be honest, is probably something I should pick up.