Over the years (and it

has been years) since this blog and our multi-year plans to sail with a young son began, I have received the occasional opinion that it would be better if we waited until we were closer to retirement age. The logic goes that our finances would be "on a firmer footing", our son would be on his own or in college, and we could "downsize" our downtown home, recoup our investments and get a nicer boat with electric hoo-hahs and all mod cons.

Putting aside some fairly large assumptions inherent in such an opinion, such as a) there's no prospect that our house will actually show a profit in 15 years' time as the general economy may be in the dumps; and b) our son, if at a university, might be ruiniously expensive if scholarships are unobtainable; and c) our health and strength would endure to that stage at such a pitch that we could, as a sailing couple, operate a 40-45 footer safely in all weathers. This isn't even taking into account that we might have living relatives both ill and old and underfunded in our care, or that diesel could be three times its current costs. Lastly, there's d) a large reason to go is to expose our son to the rest of the world while such a fleeting opportunity, historically speaking, for non-rich people, by Western standards, to do so is still open a crack, and so on.

Basically, the "go while you still can" mantra holds for us. Working like dogs until 60 or 65 in order to have a nicer Beneteau holds little appeal if other things we can't control come into play in a deleterious manner. We know more than one cruiser couple who have either commenced cruising or are planning to cruise with largely the same outlook, although many have started from differing assumptions or adequately funded pension plans.

If you wait, the opportunity may never come. The stars may fail to align.

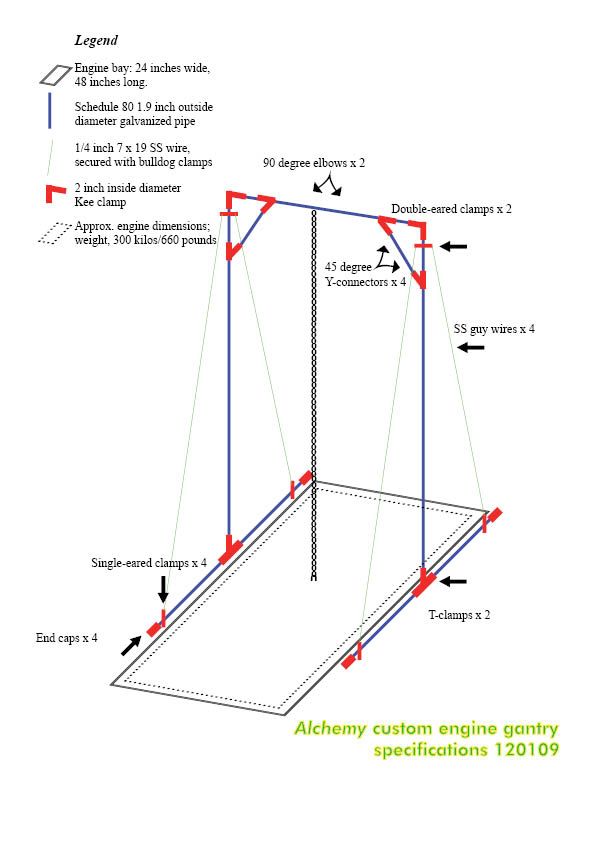

Consider our boat,

Alchemy: It was custom-built in the late '80s by a fellow who took a long time to finish it. I'm not convinced, having spoken only briefly to him on the phone, that he wanted to travel the world, but for whatever reason (age, interests changed), he owned it for 17 years and never took it into salt water, despite the fact it's

ludicriously overbuilt for the Great Lakes. See "Why do I have

eleven 5/16th inch stays?"

The second owners further fitted out the boat for a couple of years with some top-end amenities, and then received a lucrative job offer unto retirement that convinced them to give up, or at least postpone, their dream of world travel. We're therefore the third owners in 23 years of an ocean-going boat that's

not been to the ocean. We might actually push off in said direction, unless the "curse" strikes our enterprise as well. Let's keep fingers crossed, and, if necessary, sacrifice a goat against that possibility.

One of the more compelling reasons, however, to sail off that I present to well-meaning interlocutors seems to have an almost universal affect on those suggesting a more protracted run-up to passagemaking.

That reason is that I believe I will never receive a pension, and I will never actually be able to retire.

Not in the conventional, that is to say, post-1965 and pre-2008 sense. Like most humans throughout history, I will likely die in harness, which could mean a fate as ugly as the world's oldest telemarketer. My only consolation in doing so will be that I am likely to do so at an older age than the historical norm, if we can keep purifying the water and don't bugger up the air or food supply too badly.

I am also hoping that if I have to work until I snuff it, I will have no regrets and plenty of feedstock for pleasant dreams, having sailed around the world for five or so years.

Still, my outlook is not very comforting, is it? A lot of people currently cruising have pension income of some sort, and that may be well-funded, or well-funded enough that such fortunate folk may pass naturally (or simply swallow the anchor) before the piggybank runs out. Congratulations to them; I bear no grudge.

But I believe, sincerely, that

I will not be among their number. My 12 years' younger wife or 40 years' younger son?

Not a chance. The larder will be bare, and is already understocked.

Everything they have paid or will pay into my country's national pension scheme will be utterly gone (or will be devalued to the point of "gone") by the time they reach retirement age, which, if the entire house o' cards is to kept in a wobbly state of mostly upright, will be between 75 to 80 years old, and for the Greeks, 110 years old.

So I hear this:

"Wait, you are sailing off in middle age because you think pension schemes are the devil's songbook?"

Well, yes, I intend to and I do, although there are other reasons. But having invested my own money, such as it is, for many years, and having been self-employed for only a somewhat shorter period, my belief that pensions

as currently administered in my country and most, but not all, others, are a mug's game is based on two simple, and contrasting concepts.

1) Governments have treated pension funds as piggybanks at the same time as they have kept contributions artificially low to avoid alarming the peasants. Thus, the commitments far outstrip the ability to pay.

That doesn't make pensions stupid. It means that you have to have them run at total arm's length from idiot governments who can only think in four-year cycles. A pension demands the ability to count to 100 and to stick with what one learns from being able to count to 100 whether people whine and bitch or not.

2) For the same whining and bitching reasons, governments have not directly linked life expectancy to retirement age. The age of 65 was arrived at when meb (and it was mostly men who had pensions for many years) died, on average, at 67. You don't need a lot of planning or even cash to pay out two years of benefits for 40-plus years of planning, particularly as the average age of 67 implied that a lot of men kicked off years before that and got NOTHING, or just a fractional payout to a surviving spouse. My grandfather died two days before his 65th birthday in 1968, for instance. Not a penny did his widow, who lived a further 25 years, get from the pension scheme of the day. My mother died at 68; she got three years, having contributed since the age of 18: 50 years.

Now, some might say "Ah, but that's just a roll of the dice. It doesn't invalidate the pension logic." And I might agree with such a person...in principle. But pensions have long since abandoned any notion, in my view, of "principle".

These days, men in Canada live until 81 and women to nearly 84, on average, and therefore collect pensions for 16 to 25 years, as they can "retire" at 60 on a partial or at 65 on a full pension. Trouble is, having built all those universities and discouraged the trades, we aren't STARTING work until 22 or 23 (or 25 if you go for a master's or a PhD) and therefore expect to pay generous pensions (in the context of maximum years of earnings) for 20 years from a working life of 35-40 years.

So the second concept is that in order for this pie-in-the-sky pension scheme to work, we would have had to kick the retirement age to 75 about 20 years ago by upping the age of retirement by one year every two years or so. The biggest bulge in the python, demographically speaking, would have been therefore "encouraged" to put away more, and earlier, themselves, because the bareness of the cupboard marked "pension benefits" would have been more apparent earlier in the process, when we had a hope of applying some fiscal probity...instead of clapping Tinker-fucking-bell back to life.

Anyone else see a problem with this? In all of the Western democracies, save perhaps Germany (which could be sabotaged by the "Euro project" in this respect even yet) and Scandinavia, the pension-planners' "house"

cannot collect enough to pay out all those winners. Those of us who work as self-employed persons actually make a double contribution to a fucking pyramid scheme that will be sucked dry from the enormous generation of "boomers" directly ahead of us in age...and who will NEVER support pension reform...because it is not remotely in their interests to do so.

Looked upon in that light, buggering off with no income (visible to my nation's government at least) in a boat for five years is actually a break from the daily wallet-sized prison rape of living in a society that wishes to print money without doing the requisite math to make said slips representative of actual wealth. While cruising, we may not

make any money, but we get a brief absolution from pissing into a bottomless well from which we, as the currently middle-aged income earners and contributors, can never plausibly draw.

World cruising is therefore

a withdrawal of our services, and a

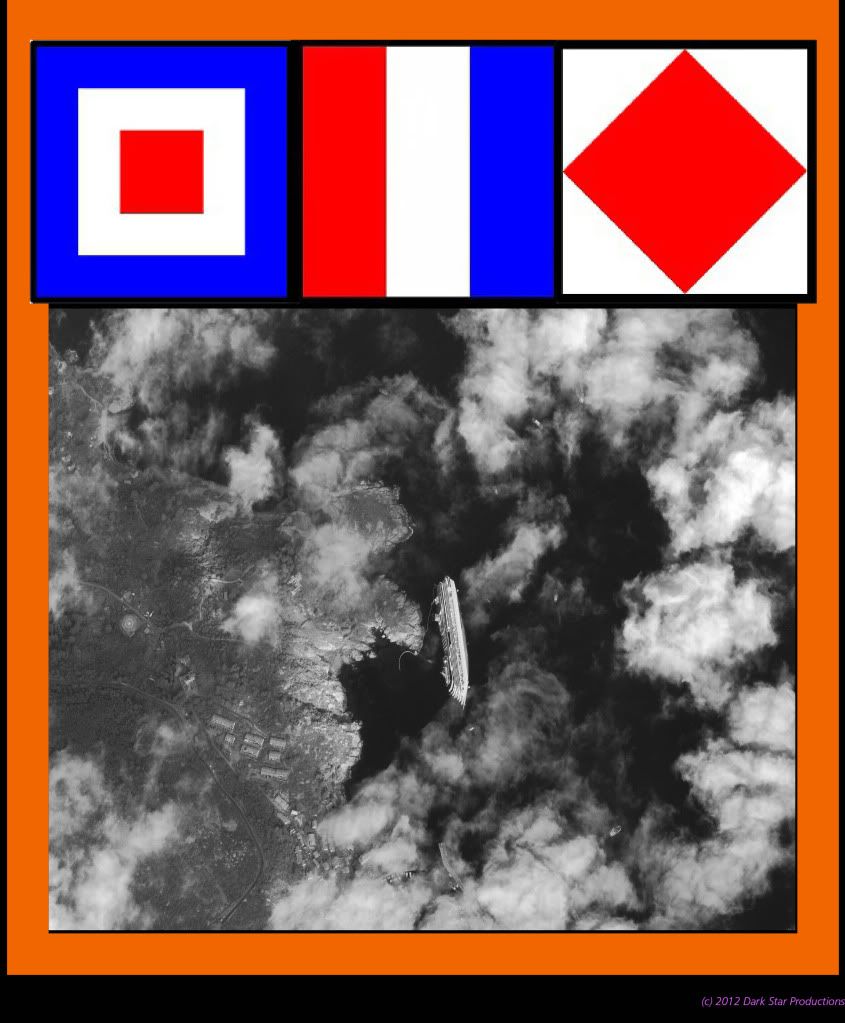

refusenik tactic, as much as it is a nice way to see the world, while there's still a world to see.

I have mentioned before that some of our ambition to make a rather unconventional trip like this was rooted in a pessimistic view of humanity's future (we should go before piracy, adrift containers and Texas-sized patches of plastic are normal in every ocean) and of the continuing degradation of the environment (see the lovely atoll nation before it's a sandbank; sail while there's still fish to catch off the stern). Add to that the compelling rationale that long-term cruising withdraws the family finances to a significant degree from the never-ending shell game of national pension schemes, and it gets harder some days to be cheerful about the prospect of casting off at all. I only thank Neptune or whatever watery deity applies that I figured this out at 40 instead of 60. I have been planning our escape accordingly, and postings such as this are "goon-baits" in the fine old Colditz tradition.

The system will only collapse more quickly if everyone figures it out for themselves. See "Europe: now".

UPDATE Dec. 14, 2011:

According to this story, my country cannot even fund its pension scheme to its own bureaucrats and other federal government workers.

"One of the figures Ottawa uses to determine its pension liability is a

moving average of past “nominal” yields on 20-year federal bonds, while

the other is an assumed return on investments of 4.2 per cent based on

averages earned since 2000.

The C.D. Howe report says the

“made-up” numbers are not realistic in today’s world of low interest

rates and low investment returns.

“Both these interest rates are

well above anything currently available on any asset that matches the

plans’ obligations,” Mr. Robson said in a news release Tuesday."

Pension plans

must be formulated on the payout side on the basis of everyone slightly outliving the forecasted draw-down. That is, if the average age of death is, say, 80, and the vast majority work until 65, you provision for 16 or 17 years of payouts, averaged out. This is because the average age of death will tend to move forward in time as people who

would have died within that period benefit from medical advances and other life-extension methods, like a more active lifestyle and a better diet.

Pensions were so much easier when people retired and dropped dead three years later from too much smoke and gravy, frankly. Now, all that time at the gym followed by salad means a lot of wiry oldsters are working stacking shelves and greeting at Walmart. It's a glimpse into the future.

Pension plans must be contributed into on the basis of the most conservative outcomes; in a low-interest, low-inflationary period, one cannot "bank" on even a pension fund's considerable buying power to outdo the market, which, as we've learned, is substantially rigged in favour of the already-rich. So if one's assumptions are too rosy (and "too rosy" is a real problem in this area of management), the pension will inevitably have less money to address an ever-expanding set of entitlements and obligations.

In sum, when the bureaucrats, who are generally assumed to have gold-plated retirement funding, start to question the imperial habit of coin clipping and currency debasement (to cite what in part did in the Roman Empire), it's time to review what we, the better washed but nonetheless vast plebian population can expect, if anything, to keep us out of the garbage bins, food banks and future auditions for "Bum Fights, 2030".