Something a little different today: This post is not another product evaluation or status update about the big steel cutter, but something about deciding to share a boat with fellow enthusiast, and putting in a few hours in order to do that right. Yes, it takes away from the hours devoted to "The Big Project", but all work and no sailing makes Jack and myself a dull sailor, and I'm pretty dull already. This post is about shiny, or at least much less chalky, things.

A recap: Faced with an market for used boats so soft as to be vaporous, I decided to keep

Valiente, my first and fibreglass boat, one more year until I could find either a buyer or a way to store it (in a shed? in a field?) for several years until we returned from the five-year trip we are two years from starting.

Having a "spare" yacht does not, in my experience, inspire sympathy, but just as the currently largely dissembled

Alchemy is near-ideal in my mind for long-range voyaging, the 1973 vintage, 33 1/2 foot Valiente is ideal for Great Lakes cruising and even club racing. Its design by the venerable C&C firm is narrow, fast and light, with a notable "stiffness" conducive to cutting through the short, square chop of our freshwater seas, and while amenities are few on this pushing 40 vessel, the ride is indeed sweet. Life after a circ may be distant, but I can still see wanting to head out with beer and sandwiches on a nice, responsive tiller-steered boat like the one I fell in love with in 1999. So I am motivated, within reason and fiscal sense, to keep this old girl in some form and fashion. People with big boats say I will never go back to a smaller one, but if I do, I could do much worse than this.

Nonetheless, I can't afford to keep two boats in either dollars or time, and so I was resolved to pay good money to leave her moldering in a nasty waterside parking lot while I figured out what to do. A series of fortunate events put a former sailor in my life who wanted to ease back into sailing. This individual, who shall remain nameless (hence Ni, or "nameless individual") because I get the sense he's a private kind of guy, has brought a lot of practical experience and a strong desire to work to the partnership, and is interested in doing the kind of stuff that, while I like the results, have never found very compelling, like making the hull look nice or rationalizing the wiring.

Long story short, we decided to split costs on a downtown marina slip and get

Valiente in running order again. Part of this isn't the usual hoses and gaskets work on which I tend to focus, but a more comprehensive restoration. What follows are a visual record of how an old, oxidized gelcoat topsides can be "brought back" via a few steps, the right product, and elbow grease. All credit to Ni here, as this was his "thing"while I was replacing valves and batteries and losing tools on the "inside".

Here's the hull after one polisher-assisted application of "Meguiar's No. 1", a semi-coarse rubbing compound in liquid form. It's already taken off much of the "age" of the 37-year-old gelcoat.

The view from the front. This was April 6th. We've had with few exceptions very good weather this spring in Toronto, allowing early starts on the boat readying front. As

Alchemy isn't launching, the decision was made to "do it right" on

Valiente, the sailing component of my cheap-ass navy. Oh, and those little chunks out of the stem will be fixed, and a bow roller I had made years back attached.

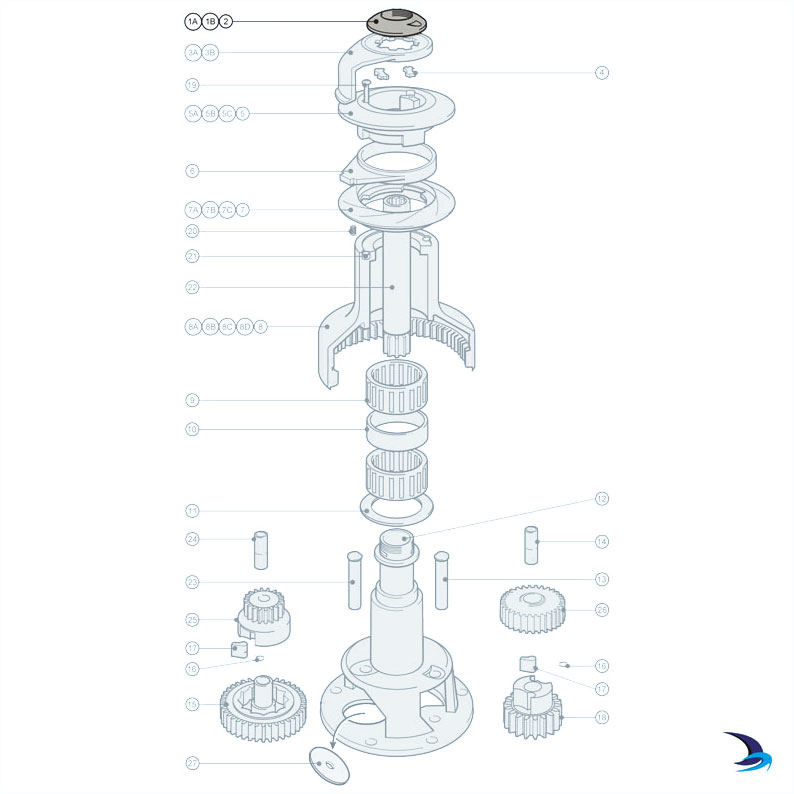

The folding prop, in need of servicing (lubrication and tightening of the Allen bolts), and a nice polish.

The finished initial polish on April 12th. Nice, no? But wait, there's

more!

The finished second polish, with Meguiar's "No. 2", on April 14th. By this stage, Ni was getting excited. I think it's clear that he likes shiny things and finds polishing meditative in a way I obviously do not. This is actually a good thing in a boat partner...to have different priorities and experiences.

Ni "took the initiative" and cleaned out the shaft strut back to the bronze of several coats of filler, bottom paint and related goo. An area that looked like a pacifier for senile lampreys became free and ready for fairing.

April 17: While I started on what would be two cans and three coats of VC-17M bottom paint, Ni continued with the fairing and tidying up of the strut and keel root areas.

Now, the proper way to do all this below-the-waterline fairing and filling stuff involves Tyvek suits, wet sandpaper and excruciating attention to detail. If one is a racer, that is. We "just cruise fast" types resolve to see how a test of a concept works before getting into

that time-pit. Not to mention expensive respirator filter elements.

Seriously, this is the most TLC the boat's had during my entire watch in the cosmetics department.

April 19th: Priming the strut prior to applying the last of the bottom paint. Nice work, Ni!

April 19: The final application and hand-polishing of "Starbrite" marine sealant/topcoat/whatever. Ni remarked that the gelcoat was "drinking" this stuff as its "pores closed", which I understand from a chemical point of view but still sounds like one of those dodgy make-up for forty-something commercials to me.

While there are some mechanical and maintenance issues to get at, we "achieved ignition" yesterday on the 20th and are more or less ready to splash the boat and make our way to the pricey but centrally located slip we've procured for this season. A pair of new batteries, a new seacock and various sealants, paints and compounds have been applied, and after a very well needed deck wash (did I mention that the canvas cover under which I usually store the boat was shredded by gales this winter, exposing the deck to the diesel soot and dirt of the adjacent recycling facility? No, I believe I did not), we'll have a boat that not only sails very well, but looks great doing it.

After a hot day down in the bowels of

Alchemy, that will make for a very nice break, as well as keeping our infrequently tested sailing skills up.

Coming soon: The

Safety at Sea seminar I attended recently, recommended rudder removal, and U.S/Canadian dollar parity and its affects on the self-equipper's budget.

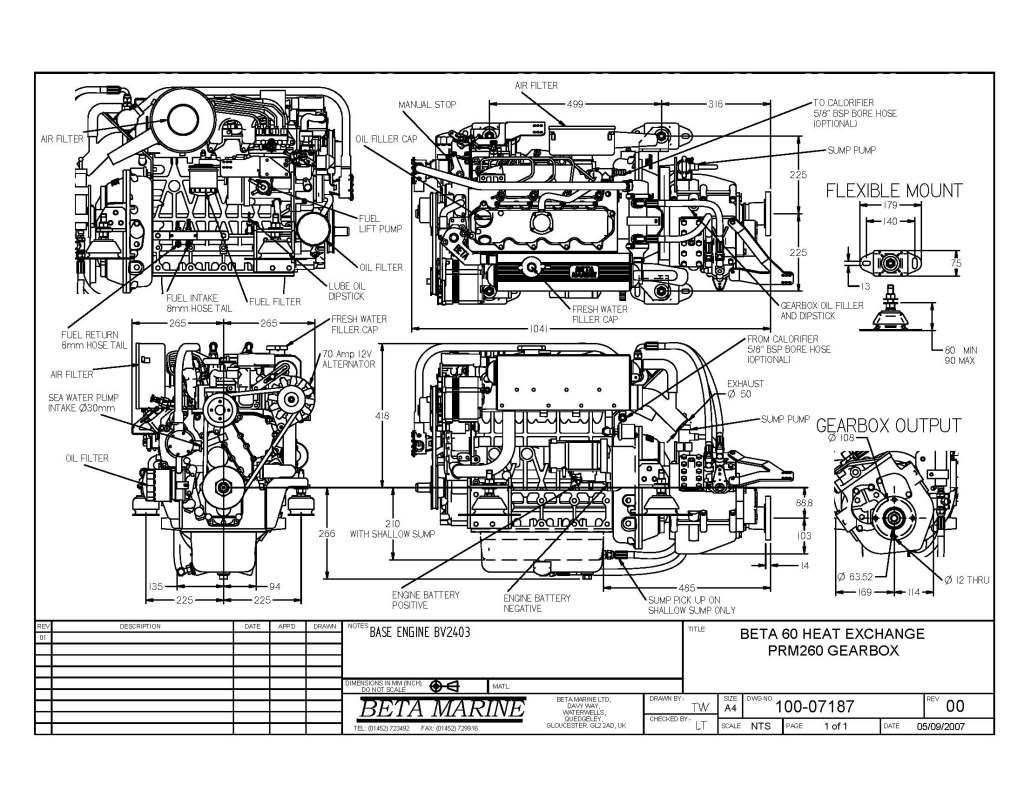

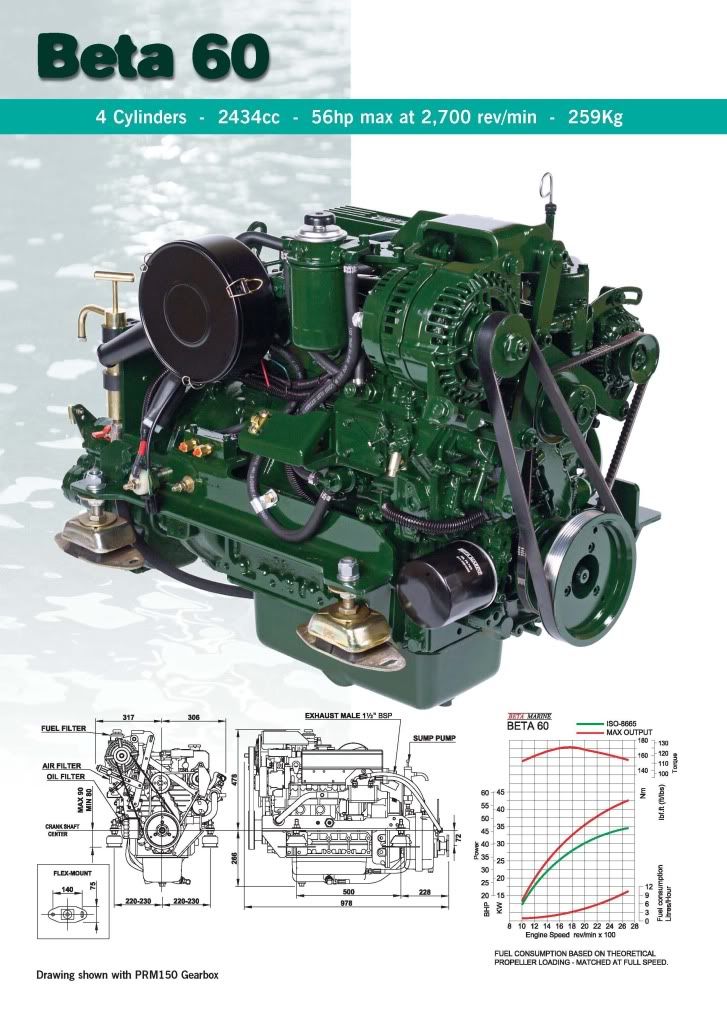

After considerable consultation and debate, I've purchased this engine for Alchemy. A fellow in my club announced himself not only as the Nanni diesel rep for Toronto (a French marinized Kubota), but as the Beta Marine rep (an English marinized Kubota).

After considerable consultation and debate, I've purchased this engine for Alchemy. A fellow in my club announced himself not only as the Nanni diesel rep for Toronto (a French marinized Kubota), but as the Beta Marine rep (an English marinized Kubota).